AGATHÓN

International Journal

of Architecture, Art and Design

ISSN (online) 2532-683X

ISSN (print) 2464-9309

Vol. 17 (2025): POVERTY (SDG 1), HUNGER (SDG 2), HEALTH AND WELL-BEING (SDG 3), QUALITY EDUCATION (SDG 4), GENDER EQUALITY (SDG 5) | Projects, research, synergies, trade-offs

Starting with this volume, the International Scientific Committee has decided to publish a series of volumes dedicated to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in September 2015 by the Member States of the United Nations (UN, 2015). These goals are promoted as a call for urgent action aimed at combining prosperity, equitable development, and the protection of our planet, while emphasising the value of cooperation and partnerships between countries, national and local governments, public institutions and private enterprises, and among civil society and individuals. However, only six years away from their target date, the call appears not to have been fully heeded, if not overlooked entirely, and, therefore, the scientific community cannot and should not avoid reflecting on ‘where we are now’, ‘where we are going’, and ‘where we might still be able to go’. A data-driven assessment of progress was made by the Global Sustainable Development Report, which, in two subsequent documents (IGS, 2019, 2023), called for an appropriate correction and an urgent acceleration of implementation policies without which humanity will face prolonged periods of crisis and uncertainty, further jeopardising the principle of ‘leaving no-one behind’ and the preservation of the entire ecosystem globally. While the 2019 Report acknowledged that progress on some goals needed to accelerate, it also affirmed that the world was largely on the right track. In contrast, the 2023 Report paints a far more troubling picture, highlighting not only insufficient acceleration on several goals, but also regression in critical areas such as food security, climate action, and biodiversity protection.

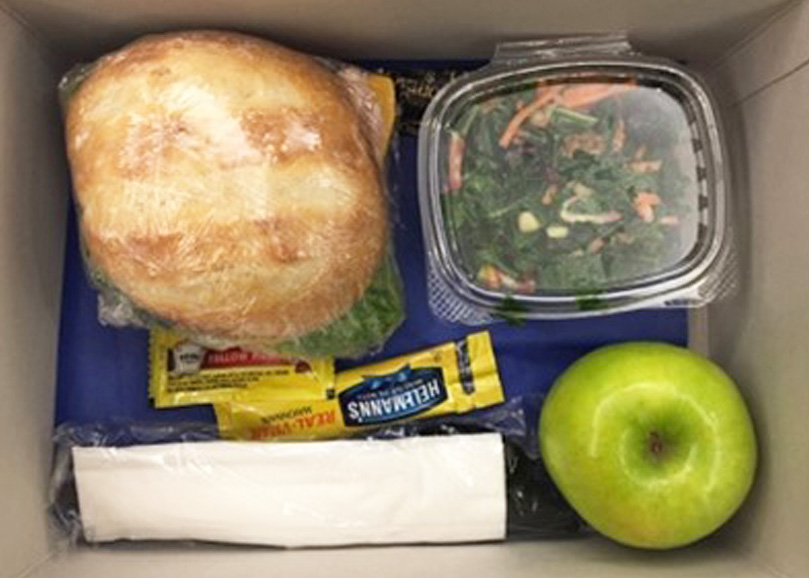

Against this backdrop, it seems all the more urgent to assess ‘what needs to be done and how it can be done strategically’ considering that, as advanced by the United Nations when defining the SDGs (UN 2015) and confirmed by the 2019 Report itself, most of the goals are synergistic, and that the social and environmental ones, in particular, have systemic impacts that drive overall progress towards achieving all the other SDGs. Although the scientific literature on the interconnections between the SDGs has grown rapidly, and numerous studies claim that synergies outweigh trade-offs, there is a high and not yet fully investigated and harnessed potential to achieve simultaneous progress on multiple goals through integrated planning and appropriate strategies in particular Goals 1 (no poverty) 2 (zero hunger) 3 (good health and well-being) 4 (quality education) 5 (gender equality) 6 (clean water and sanitation) 7 (affordable and clean energy) and 17 (partnerships for the goals) are identified as strategic as they are capable of generating benefits on many other goals (Barbier and Burgess, 2019; Randers et alii, 2019; Pham-Truffert et alii, 2020). Nevertheless, SDG achievement necessarily imposes compromises that often result in critical issues that are not resolved by current practices. Examples of this are the actions and strategies promoting Goal 2 (eradicating poverty), where land cultivation and intensive agricultural practices generate soil degradation pollution and loss of biodiversity, or those related to Goal 8 (decent work and economic growth), where uncontrolled growth and development lead to use of natural resources beyond sustainable limits. These critical issues are confirmed by the recent Global Sustainable Development Report (IGS, 2023), according to which progress on Goals 14 (life below water) and 15 (life on land) is more negatively affected by progress in other areas than positively influenced by specific actions.

It should be noted that the nature of the connections in terms of synergies and trade-offs between the different goals can vary significantly depending on the ‘space’ and ‘time’ dimensions but also within different income levels and population groups: scientific literature, for example, shows how poverty reduction generates overall positive effects on the 2030 Agenda in low-income countries, but also how integrated strategies that address climate change and inequalities are more decisive in achieving the goals in high-income countries. The latter, however, seem to face more trade-offs than the others, which may partly explain their delay in achieving the SDGs (Lusseau and Mancini, 2019; Nilsson et alii, 2022; Kostetckaia and Hametner, 2022). Moreover, it should not be overlooked that many interconnections have a cross-border character: according to the OECD (2019, 2024), 57% of the 169 attainable targets in one country can have spillover effects in other regions or countries of the world, crossing national borders through flows of capital, goods, and human and natural resources and positively or negatively influencing their future and development prospects. In this sense, while we cannot afford to generate negative and costly impacts elsewhere, the failure to recognise potential positive spillovers in ‘far away’ places is a loss of opportunity. All these variables mean that it is essential to thoroughly understand the interconnections in terms of synergies and trade-offs. This understanding is fundamental not only to guide scientific research but also to identify effective ways to reduce trade-offs, address uncertainties, and capitalise on context-specific opportunities, supporting strategic decision-making and fostering transformative interventions. Many tools and methods are now available for the integrated analysis of the Goals, for decision support, and to monitor progress (Barquet et alii, 2022), such as the toolbox with guidelines for the ex-ante evaluation of impacts promoted by the European Commission (2023). However, a greater ability to think in systems terms is required, i.e. to consider the systemic effects of policies, pathways, measures and actions; this is the best possible approach to optimising the interactions of the SDGs. Integrating the theme of the SDGs with Digital Humanities also opens up innovative perspectives that can strengthen synergies between different fields of knowledge and help minimise trade-offs among the SDGs themselves. By providing a new framework in which digital tools and methodologies are applied to the study of the humanities, Digital Humanities promote a systemic and integrated approach to addressing global challenges and analysing the complex dynamics between different goals. They offer various ways of monitoring, understanding, and improving not only the interactions among the Sustainable Development Goals themselves but also the relationships between these goals and the strategies and actions designed to achieve them.

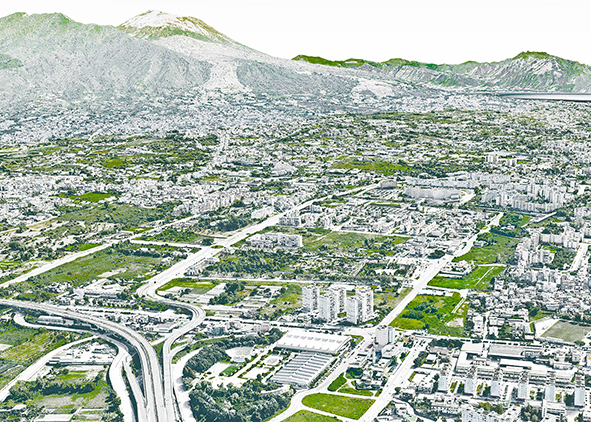

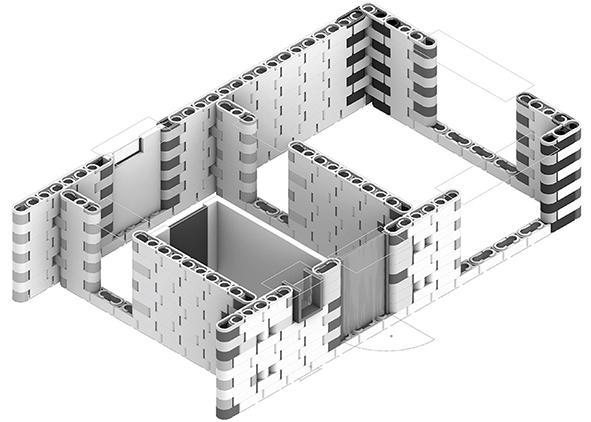

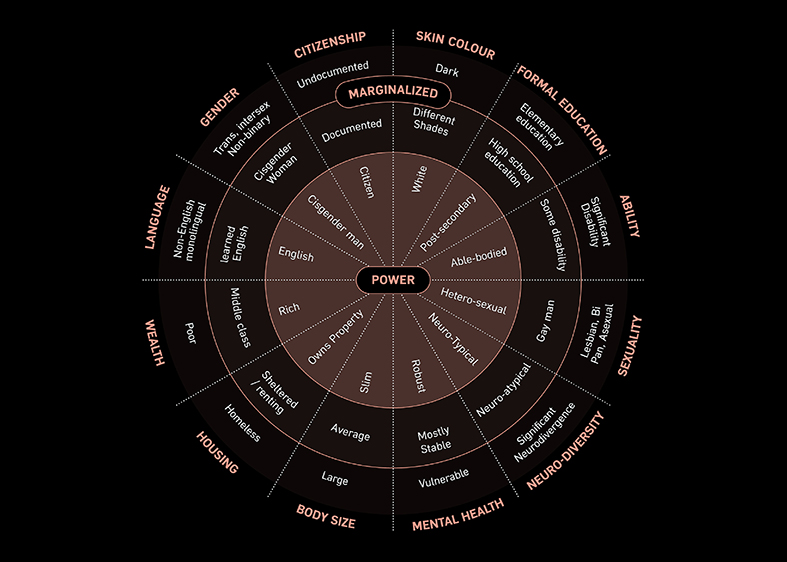

On the basis of these reflections, volume 17 of AGATHÓN, addressing the disciplinary areas of Landscape, Urban Planning, Architectural and Urban Composition, Engineering, Architectural Technology, Design, Restoration and Rehabilitation, and Representation, has selected a series of contributions on the theme ‘Poverty (SDG 1), Hunger (SDG 2), Health and Well-being (SDG 3), Quality Education (SDG 4), and Gender Equality (SDG 5) | Projects, Research, Synergies, Trade-offs’, intending to foster an open discussion through the collection of essays and critical reflections, research and experimentation, projects and interventions. These contributions adopt an innovative, multidisciplinary, and multi-scalar approach, using systemic methods and addressing aspects of process – design, production or implementation, and management – as well as methodologies and models for ex-ante and ex-post evaluation. The objective is to overcome limitations, gaps, and barriers, while enhancing synergies and reducing trade-offs with other goals. In fact, the built environment interacts with every goal (Thorne and Duran, 2016) while at the same time remaining part of the current challenges. On the one hand, it is a large consumer of energy and natural resources and a relentless producer of harmful gases and waste; on the other hand, how we act can exacerbate inequalities and affect human health. This is particularly relevant in cities, whose importance in terms of both vulnerability and opportunities for growth is underlined in all SDGs, especially considering that around 70% of the world’s population will live in urbanised areas by 2050 (UN-Habitat, 2022). Once again, there is an urgent need for strategically planned, designed and implemented anthropogenic action consistent with multiple SDGs that can ensure the improvement of a community’s overall quality of life, sustainability, social equity, health and resilience. With this in mind, the essays and research published address the first five Sustainable Development Goals, in the awareness that poverty, hunger, health and well-being, quality education, and gender equality are not separate domains but interconnected fields of action and reflection, both among themselves and with the other Goals. On these, design – understood in its broadest sense, including urban planning, landscape, architecture, and technology – can and must exert a systemic influence. The present editorial attempts to mirror this complexity, highlighting – for each contribution – themes addressed, disciplinary field of reference, project scales involved, types of action employed, and, above all, the importance and transferability of the solutions tested.

The contributions published in volume 17 of AGATHÓN demonstrate that design, understood in its broadest and transdisciplinary sense, is not merely a tool for representation or technical response, but a powerful strategic lever for addressing the challenges of the 2030 Agenda in a systemic and integrated way. Poverty, hunger, health, education and gender equality, like other SDGs, should not be addressed as isolated issues, but as interconnected thresholds, crossing the bodies, spaces, everyday practices and cultural infrastructures of our societies. Universities, research and design today have the responsibility not only to observe, but also to act, producing knowledge, building operational tools and activating co-design networks with communities, institutions and territories. The essays, research and case studies presented offer replicable and adaptable views and models and speak the language of intersectionality, proximity and design responsibility. To truly accelerate the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, it is essential to overcome numerous barriers. These include cultural barriers, which prevent inequalities from being understood as spatial and design-related constructs; regulatory barriers, which hinder social and technological innovation; operational barriers, linked to the lack of tools, data, and multi-level governance; and epistemic barriers, which continue to regard design as a neutral or secondary activity rather than as a genuine driver of change. The challenge, therefore, is twofold: on the one hand, to build a more porous academic sphere, capable of connecting with the real needs of territories and translating research into tangible impact; on the other, to promote an idea of a design that can act sustainably and equitably on the thresholds of economic self-sufficiency, food, housing, care, learning, and gender equality, generating cohesion, resilience, and justice. Designing for the SDGs does not simply mean aligning with a global framework; it means recognising that every design act is, now more than ever, a political, ecological, and social act. In this sense, the published contributions already point to a direction: a new alliance between knowledge and transformation, between research and community, and between space and justice.