Relazioni modulari negli spazi di lavoro – Approcci data-driven per progettarne il futuro

DOI:

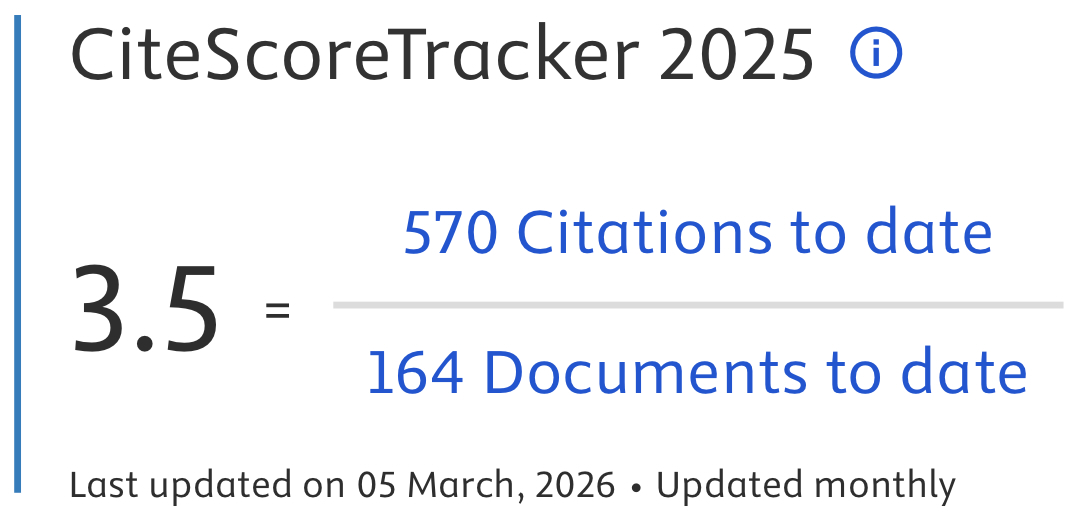

https://doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/14242023Parole chiave:

luogo di lavoro, futuro del lavoro, progettazione guidata dai dati, modelli comportamentali, interazione uomo-spazioAbstract

Il contributo esplora la natura evolutiva degli spazi di lavoro in un contesto di flessibilità tecnologica e sociale. La dimensione modulare dell’ufficio viene analizzata attraverso il cambiamento delle soluzioni spaziali sulla base di cambiamenti socioculturali che hanno influenzato modelli gestionali e scelte progettuali. In seguito, l’analisi si concentra sull’efficacia di approcci data-driven per esplorare i contesti lavorativi: i dati sono uno strumento utile a comprendere le esperienze e le percezioni dei dipendenti per elaborare soluzioni volte a migliorare il benessere all’interno degli spazi di lavoro. Obiettivo è delineare la trasformazione dell’ufficio da modulo chiuso e individualista a sistema aperto e condiviso in cui i dati svolgono un ruolo fondamentale nella definizione del futuro degli spazi di lavoro.

Info sull'articolo

Ricevuto: 10/09/2023; Revisionato: 16/10/2023; Accettato: 22/10/2023

Downloads

##plugins.generic.articleMetricsGraph.articlePageHeading##

Riferimenti bibliografici

Ahrentzen, S. B. (1987), Blurring Boundaries – Socio-Spatial Consequences of Working at Home, Center for Architecture and Urban Planning Research Books. [Online] Available at: dc.uwm.edu/caupr_mono/36 [Accessed 15 October 2023].

Baiardi, L. (2018), “Un esempio di coworking e smart living a Milano | An example of coworking and smart living in Milan”, in Agathón | International Journal of Architecture, Art and Design, vol. 4, pp. 137-144. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/4172018 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Bencivenga, M. and Camocini, B. (2022), “Post-pandemic scenarios of office workplace – New purposes of the physical spaces to enhance social and individual well-being”, in Dominoni, A. and Scullica, F. (eds), Designing Behaviours for Well-being Spaces – How Disruptive Approaches Can Improve Living Conditions, FrancoAngeli, Milano, pp. 90-111. [Online] Available at: hdl.handle.net/11311/1202333 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Bird, M. (2020), “Enter the Cube Farm”, in MIT Sloan, 25/11/2020. [Online] Available at: sloanreview.mit.edu/article/enter-the-cube-farm/ [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Budd, C. (2001), “The Office – 1950 to the Present”, in Antonelli, P. (ed.), Workspheres – Design and Contemporary Work Styles, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, pp. 26-35. [Online] Available at: moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_168_300133807.pdf [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Casiddu, N., Burlando, F., Nevoso, I., Porfirione, C. and Vacanti, A. (2022), “Beyond personas – Il Machine Learning per personalizzare il progetto | Beyond personas – Machine Learning to personalise the project”, in Agathón | International Journal of Architecture Art and Design, vol. 12, pp. 226-233. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/12202022 [Accessed 16 October 2023].

Danielsson, C. B. and Bodin, L. (2009), “Difference in satisfaction with office environment among employees in different office types”, in Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, vol. 26, issue 3, pp. 241-257. [Online] Available at: jstor.org/stable/43030872 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

De Been, I. and Beijer, M. (2014), “The influence of office type on satisfaction and perceived productivity support”, in Journal of Facilities Management, vol. 12, issue 2, pp. 142-157. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1108/JFM-02-2013-0011 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Ebert, I., Wildhaber, I. and Adams-Prassl, J. (2021), “Big Data in the workplace – Privacy Due Diligence as a human rights-based approach to employee privacy protection”, in Big Data & Society, vol. 8, issue 1. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1177/20539517211013051 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Edgell, S., Gottfried, H. and Granter, E. (2016), The SAGE handbook of the Sociology of Work and Employment, Sage Publications Ltd, London-Thousand Oaks.

Fagnoni, R. (2023), “In certezza – Fare ricerca in design nell’era dei dati”, in Casarotto, L., Costa, P., Fagnoni, R. and Sinni, G. (eds), Il potere del dato, Ronzani Editore, Vicenza, pp. 21-33.

Fagnoni, R. and Olivastri, C. (2019), “Hardesign vs Softdesign”, in Agathón | International Journal of Architecture Art and Design, vol. 5, pp. 145-152. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/5162019 [Accessed 12 October 2023].

Gaiardo, A., Remondino, C., Stabellini, B. and Tamborrini, P. (2022), Il design è innovazione sistemica – Metodi e strumenti per gestire in modo sostenibile la complessità contemporanea – Il caso Torino, LetteraVentidue, Siracusa.

ILO – International Labour Organization (2020), Covid-19 – Guidance for Labour Statistics Data Collection. [Online] Available at: ilo.org/global/statistics-and-databases/publications/WCMS_747075/lang--en/index.htm [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Johansen, R., Press, J. and Bullen, C. V. (2023), Office Shock – Creating better futures for working and living, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland (CA).

Kim, J., Candido, C., Thomas, L. and de Dear, R. (2016), “Desk ownership in the workplace – The effect of non-territorial working on employee workplace satisfaction, perceived productivity and health”, in Building and Environment, vol. 103, pp. 203-214. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1016/J.BUILDENV.2016.04.015 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Marino, C. (2022), “Metodi e strumenti per il rilievo olistico”, in Gaiardo, A., Remondino, C., Stabellini, B. and Tamborrini, P. (eds), Il design è innovazione sistemica – Metodi e strumenti per gestire in modo sostenibile la complessità contemporanea – Il caso Torino, LetteraVentidue, Siracusa. pp. 82-85.

McKinsey & Company (2021), The future of work after Covid-19. [Online] Available at: mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Messenger, J. C. and Gschwind, L. (2016), “Three generations of Telework – New ICTs and the (R)evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office”, in New Technology, Work and Employment, vol. 31, pp. 195-208. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12073 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Microsoft (2022), Microsoft New Future of Work Report 2022 – A summary of recent research from Microsoft and around the world that can help us create a new and better future of work. [Online] Available at: microsoft.com/en-us/research/uploads/prod/2022/04/Microsoft-New-Future-Of-Work-Report-2022.pdf [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Microsoft (2021), The New Future of Work – Research from Microsoft into the Pandemic’s Impact on Work Practice. [Online] Available at: microsoft.com/en-us/research/uploads/prod/2021/01/ NewFutureOfWorkReport.pdf [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Propst, R. (1968), The Office – A facility based on change, Herman Miller, Zeeland.

Rafaeli, A. and Vilnai-Yavetz, I. (2004), “Instrumentality, aesthetics and symbolism of physical artifacts as triggers of emotion”, in Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, vol. 5, issue 1, pp. 91-112. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1080/1463922031000086735 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Sánchez-Monedero, J. and Dencik, L. (2019), The datafication of the workplace. [Online] Available at: datajusticeproject.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/30/2019/05/Report-The-datafication-of-the-workplace.pdf [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Stallworth, O. E. and Kleiner, B. H. (1996), “Recent developments in office design”, in Facilities, vol. 14, issue 1/2, pp. 34-42. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1108/02632779610108512 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Taskin, L., Parmentier, M. and Stinglhamber, F. (2019), “The dark side of office designs – Towards de-humanization”, in New Technology Work and Employment, vol. 34, issue 3, pp. 262-284. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12150 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

van der Voordt, T. and Maarleveld, M. (2006), “Performance of office buildings from a user’s perspective”, in Ambiente Costruido, vol. 6, issue 3, pp. 7-20. [Online] Available at: resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:efee8ad6-5449-423d-904d-dbad30bf5aa9 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Wohlers, C. and Hertel, G. (2017), “Choosing where to work at work – Towards a theoretical model of benefits and risks of activity-based flexible offices”, in Ergonomics, vol. 60, issue 4, pp. 467-486. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2016.1188220 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Zerella, S., von Treuer, K. and Albrecht, S. L. (2017), “The influence of office layout features on employee perception of organizational culture”, in Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 54, pp. 1-10. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.08.004 [Accessed 11 October 2023].

Zurlo, F. (2019), “Designerly Way of Organizing – Il Design dell’organizzazione creativa | Designerly Way of Organizing – The Design of creative organization”, in Agathón | International Journal of Architecture Art and Design, vol. 5, pp. 11.20. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/522019 [Accessed 19 October 2023].

##submission.downloads##

Pubblicato

Come citare

Fascicolo

Sezione

Categorie

Licenza

Copyright (c) 2023 Paolo Tamborrini, Sofia Cretaio

TQuesto lavoro è fornito con la licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione 4.0 Internazionale.

AGATHÓN è pubblicata sotto la licenza Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC-BY).

License scheme | Legal code

Questa licenza consente a chiunque di:

Condividere: riprodurre, distribuire, comunicare al pubblico, esporre in pubblico, rappresentare, eseguire e recitare questo materiale con qualsiasi mezzo e formato.

Modificare: remixare, trasformare il materiale e basarti su di esso per le tue opere per qualsiasi fine, anche commerciale.

Alle seguenti condizioni

Attribuzione: si deve riconoscere una menzione di paternità adeguata, fornire un link alla licenza e indicare se sono state effettuate delle modifiche; si può fare ciò in qualsiasi maniera ragionevole possibile, ma non con modalità tali da suggerire che il licenziante avalli l'utilizzatore o l'utilizzo del suo materiale.

Divieto di restrizioni aggiuntive: non si possono applicare termini legali o misure tecnologiche che impongano ad altri soggetti dei vincoli giuridici su quanto la licenza consente di fare.

Note

Non si è tenuti a rispettare i termini della licenza per quelle componenti del materiale che siano in pubblico dominio o nei casi in cui il nuovo utilizzo sia consentito da una eccezione o limitazione prevista dalla legge.

Non sono fornite garanzie. La licenza può non conferire tutte le autorizzazioni necessarie per l'utilizzo che ci si prefigge. Ad esempio, diritti di terzi come i diritti all'immagine, alla riservatezza e i diritti morali potrebbero restringere gli usi del materiale.