Embodied computation and spatiomateriality – Exploring complexity through cybermodelling

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.19229/2464-9309/16162024Keywords:

cybermodelling, spatiomateriality, symbiotic modelling, phenomenology, physical modelsAbstract

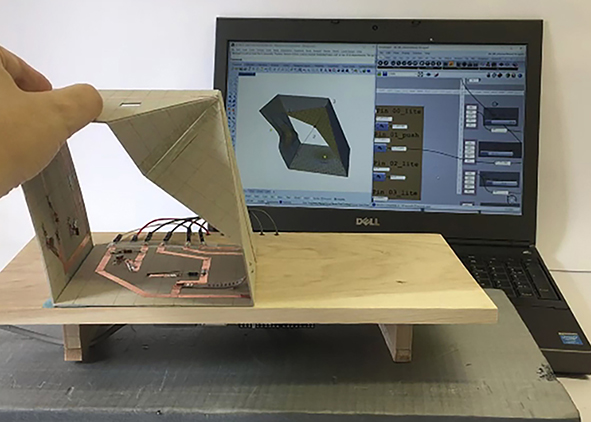

To improve its effectiveness, today’s digital design requires ‘bounded complexity’ due to the nature of the parameters involved in modelling, creating a balance between the complexity of the design problem and the tool. In addition to parameters related to form and context, a third element emerges, ‘spatiomateriality’, reflecting the connection between objects and space in physical making, as materials respond directly to changes induced by the context. This study explores a new way of using spatiomateriality through an innovative digital-analogue interface called ‘cybermodelling’: by linking real-time environmental data to digital models, cybermodelling creates ‘live’ models that react to changing conditions, generating digitised spatiomateriality. Such computational design environments support phenomenological aspects of form and space by integrating real and virtual spheres.

Article info

Received: 11/09/2024; Revised: 14/10/2024; Accepted: 16/10/2024

Downloads

Article Metrics Graph

References

Bennett, J. (2004), “The Force of Things – Steps Towards an Ecology of Matter”, in Political Theory, vol. 32, issue 3, pp. 347-372. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1177/0090591703260853 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Čahtarević, R. and Proho, A. (2019), “Geometric modelling and complexity – A conceptual approach in architectural design and education”, in Spatium, vol. 42, pp. 35-40. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.2298/SPAT1942035C [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Carpo, M. (2023), “Digitally Intelligent Architecture Has Little to Do with Computers (And Even Less with Their Intelligence)”, in ARQ (Santiago), vol. 113, pp. 19-31. [Online] Available at: dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-69962023000100018 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Carpo, M. (2017), The Second Digital Turn – Design Beyond Intelligence, The MIT Press, Cambridge.

Carpo. M. (2011), The Alphabet and the Algorithm, The MIT Press, Cambridge.

Colombino, L. and Childs, P. (2022), “Narrating the (non)human – Ecologies, consciousness and myth”, in Textual Practice, vol. 36, issue 3, pp. 355-364. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2022.2030097 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

DeLanda, M. (2015), “The new materiality”, in Architectural Design, vol. 85, issue 5, pp. 16-21. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1002/ad.1948 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Gandia, A., Iverson-Radtke, A., Payne, A. and Gupta, R. (2023), “Hybrid Making, Physical Explorations with Computational Matter”, in Crawford, A., Diniz, N., Beckett, R., Vanucchi, J. and Swackhamer, M. (eds), ACADIA 2023 – Habits of the Anthropocene – Scarcity and Abundance in a Post-Material Economy – Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference for the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA) – University of Colorado, Denver (US), October 26-28, 2023, vol. III, pp. 195-200. [Online] Available at: papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/acadia23_v3_195.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Hanna, R. and Paans, O. (2021), “Thought-Shapers”, in Cosmos and History | The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 17, issue 1, pp. 1-72. [Online] Available at: cosmosandhistory.org/index.php/journal/article/view/923 [Accessed 29 November 2024].

Harman, G. (2018), Object-Oriented Ontology – A New Theory of Everything, Penguin Books Ltd., London.

Holland, J. H. (1992), Complex Adaptive Systems, in Daedalus, vol. 121, issue 1, pp. 17-30.

Ingold, T. (2007), “Materials against materiality”, in Archaeological Dialogues, vol. 14, issue 1, pp. 1-16. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.1017/S1380203807002127 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Iverson-Radtke, A. (2022), Rabbithole to hybrid – Finding Digital Spatiomateriality Through Hybrid Modelling, Doctoral Thesis, Technical University of Berlin, Germany. [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-15983 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Jacquet, B. and Giraud, V. (eds) (2012), From the Things Themselves – Architecture and Phenomenology, Kyoto University Press, Kyoto.

Jahn, G., Morgan, T. and Roudavski, S. (2014), “Mesh agency”, in Gerber, D., Huang, A. and Sanchez, J. (eds), ACADIA 2014 – Design Agency – Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA), USC School of Architecture, Los Angeles (US), October 23-25, 2014, Riverside Architectural Press, Cambridge (CA), pp. 135-144. [Online] Available at: papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/acadia14_135.content.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Lynn, G. (1999), Animate Form, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Menges, A. (2007), “Computational Morphogenesis – Integral Form Generation and Materialization Processes”, in Okeil, A., Al-Attili, A. and Mallasi, Z. (eds), Em’body’ing Virtual Architecture – The Third International Conference of the Arab Society for Computer Aided Architectural Design (ASCAAD 2007), Alexandria, Egypt, 28-30 November 2007, pp. 725-744. [Online] Available at: papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/ascaad2007_057.content.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Morton, T. (2013), Hyperobjects – Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Paans, O. (2022), “Ontogenesis as Model for Design Processes”, in Lockton, D., Lenzi, S., Hekkert, P., Oak, A., Sádaba, J. and Lloyd, P. (eds), DRS 2022 – Bilbao, Spain, 25 June-3 July, 2022, Design Research Society, London, pp. 1-16 [Online] Available at: doi.org/10.21606/drs.2022.280 [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Paans, O., Pasel, R. and Ehlen, B. (2019), “Architectural Representation, the Controlled Future and Spatial Practice”, in Tofte, A. E., Rönn, M. and Wergeland, E. S. (eds), Reflecting Histories and Directing Futures, Proceedings Series 2019, vol. 1, Nordic Academic Press of Architectural Research, Förlagssystem, pp. 203-228. [Online] available at: adk.elsevierpure.com/ws/portalfiles/portal/63417097/115_20_PB.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Picon, A. (2004), “Architecture and the Virtual – Towards a New Materiality”, in PRAXIS, vol. 6, pp. 114-121. [Online] Available at: celop.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/97219107/Picon-Architecture%20and%20the%20Virtual,%20PRAXIS.pdf [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Pye, D. (1968), The Nature and Art of Workmanship, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Simondon, G. (2017), On the mode of existence of technical objects [or. ed. Du mode d’existence des objets techniques, 1958], University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Spuybroek, L. (2011), The Sympathy of Things – Ruskin and the Ecology of Design, V2_Publishing, Rotterdam.

Traldi, L. (2021), “Il design computazionale – Cos’è e perché dovremmo occuparcene secondo Arturo Tedeschi”, in design@large, 03/11/2021. [Online] Available at: designatlarge.it/il-design-computazionale-cose-spiegato-da-arturo-tedeschi/ [Accessed 30 September 2024].

Wolfram, S. (2002), A new kind of science, Wolfram Media, Champaign.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Aileen Iverson-Radtke, Otto Paans

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This Journal is published under Creative Commons Attribution Licence 4.0 (CC-BY).

License scheme | Legal code

This License allows anyone to:

Share: copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format.

Adapt: remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

Under the following terms

Attribution: Users must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made; users may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses them or their use.

No additional restrictions: Users may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

Notices

Users do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation.

No warranties are given. The license may not give users all of the permissions necessary for their intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material.